February 15th, 2017 was my 5th year anniversary of joining dotCloud/Docker. I have been thinking a lot about those 5 years at Docker, and thought it would make for a good blog post. This is going to be fairly long, but I think it will be worth it to see how Docker progressed over time.

How I got hired

Before I can explain how I got the job, I need to first give a little background. Before working at dotCloud/Docker I worked for a startup called CashStar. At CashStar I was the first engineer hired to build the SaaS product they were developing. When I got there, they only had a powerpoint presentation and a half working demo. This was good because it meant I had the freedom to do what I wanted and pick the technologies that I felt were best for the job. I decided on a typical Linux stack with the following as my base: Linux, Python/Django, MySQL. This stack worked very well for what we were doing. The only change I might make if I had to do it again is switch out MySQL with PostgreSQL.

Skip forward a couple of years and we had a nice product with big customers, and a good size team to support it. Thanksgiving to Christmas is our busy time of year, and then things slow down after new years. This was a good time to review the previous year and see what our pain points were and start planning our roadmap for the next year. One of the pain points we were having was around deploying our applications to our servers. Around the same time PaaS’s started to become popular, and I started to do some research on the different python PaaS’s on the market, in hopes of finding out how they work. So that I could remember what I found, I wrote a blog post for each one, with my notes. One of those blog posts was for a new PaaS called dotCloud. I really liked what they were doing, so I started following them, and trying to figure out how they did things so that I could build my own internal PaaS at CashStar.

Then one day I came across this tweet:

So you like automating the deployment and scaling of a large application? How about hundreds of thousands of them? jobs+sre@dotcloud.com

— dotCloud (@dot_cloud) December 21, 2011

I wasn’t looking for a job, but I’m always on the lookout for what is available, because you never know when the next great opportunity is going to present itself. I sent in an email to see if they were interested in a remote employee, and they said they were, and so I interviewed for the job. Over the course of the next week or so, I meet with a few people, and everyone was really awesome, and I was able to get a better understanding on how they built their PaaS. In an interview with Jérôme Petazzoni was the first time I had ever heard of Linux Containers. Not knowing anything about Linux Containers, I quickly did research so that I could be prepared for the next interview in case they asked me anything about them. I learned a few things quickly:

- There wasn’t much documentation, and what documentation there was, was very limited and low level. (not for the faint of heart)

- This was really cool stuff

- It was fairly new, and only supported in the latest kernels

- It was very hard to use

Around the same time I was trying to figure out a better way to package python application, so that they were more like Java applications (War files), and the more I read about linux containers, and talking with the dotCloud folks, the more I realized that this is the future.

After talking with everyone at dotCloud, they made me an offer. I had a good thing at CashStar and before I left, I wanted to make sure this was the right move, before I quit my job to work remotely for a small startup in San Francisco, where I only met the people a few times over google hangout. My wife and I were suppose to go to Florida for vacation, we decided to cancel that trip and instead fly to San Francisco on our own dime, to meet the dotCloud folks in person. I wanted to hang out with the team and get to know them a little more, before I decided to take the job. We also wanted to see if San Francisco would be a good place to move too, if it came to that.

After sitting with Solomon Hykes for a few hours while he talked about his vision of the future, I had decided this was the place for me, and I signed my offer letter that night. When I came back home, I gave CashStar my notice.

Docker Office

The office was pretty sweet, it was setup like a jungle. It was even featured on TechCrunch Cribs. Check out the video It had everything from big bean bags, 100’s of plants, and a pet tortoise named Gordon

Gordon the office mascot

When I was first hired, everyone was given a Nerf gun, so that you can defend yourself when working in the jungle. This was fun for a little while, but we soon had Nerf darts everywhere, and people got tired of picking them up. We quickly replaced the Nerf guns with headphones for all new employees.

Site Reliability Engineer (SRE) at dotCloud

My first job at dotCloud was as a Site Reliability Engineer for the PaaS, and Jerome Petazzoni was my manager. There was one other remote person also on the team, his name was Charles Hooper. If you are not sure what an SRE is, or does, there a SRE book that some SRE’s from Google just put out, it is a good read, check it out.

An SRE at dotCloud was basically responsible for making sure that the platform was always up and running, and if there was an issue, to help fix the issue, and prevent the same issue from happening again.

Here is what I did on a typical day:

- login, check IRC, and email to see what happened the night before.

- check nagios to see if there are any active alerts.

- Fix nagios issues

- check support tickets

- work on any projects

- meetings (stand up, etc)

I can’t remember why any more, but I did something Solomon really liked, and to show his appreciation, he made me my very own SRE badge. This is one of the cooler awards I have gotten at a company.

Projects

On top of your normal every day tasks, everyone had projects that they worked on to help improve dotCloud. Here are some of the projects I worked on.

pypi mirrors

On dotCloud the way we handled deploys was like this. You would push your code to us, it could be via git, rsync, etc and then we would take that code, read your config file, and build up a container image, which we would use to deploy to the different hosts.

As part of your config you can install dependencies, with the python service, this would be done using pip, and it would pull down the python packages from pypi. 5 years ago, there were stability issues with pypi, and they recommended that you used the --use-mirrors

flag for pip, this would allow you to use an official mirror so it will cause less damage if one of the mirrors go down. Worse case you try again.

We built this into our python service, with retry logic, to handle if the mirror we ended up on failed. This worked well, but for some reason we would end up where some deploys would work, and others would not. After digging into this some more, it was because some of the official pypi mirrors were not in sync with the master. If you picked an older package, you were fine, but if you picked one that was new, it was luck of the draw if you ended up on a mirror that was up to date.

After some research I found out that there was no easy way to see if a mirror was out of date or not. The mirrors were maintained by volunteers and there was no monitoring setup. I quickly took an audit of the mirrors and found out that more than half were out of date, and some hadn’t been updated in months. To monitor the mirrors better I created a library, and a website.

Now that we had visibility into the problem, it was easier to see what was wrong. I contacted the people in charge of the mirrors that were out of sync, and when one of the mirrors had no owner, I took over maintenance on it. After a few weeks, we had all of the mirrors up to date, and with the new website, it would let us know if one of the mirrors got into a bad state again.

A few years ago, pypi moved away from using mirrors and now uses a CDN, so this isn’t as useful, but it was a good learning experience on how all of this infrastructure worked, and it would come in handy when building the Docker registry.

AppTracker and Packer

At dotCloud, we tried to run as much of the dotCloud infrastructure on top of dotCloud, but eventually there needed to be a layer between the host and the platform. This layer was important, and really hard to upgrade. dotCloud was written as a bunch of different micro services, and when we needed to upgrade the platform, it was a big task.

Originally, the way the platform was deployed, was with a fabric script that would bootstrap the node, bring up the services, and add it to the cluster. Once it was up and running, it would start to accept work, and new services would be deployed to it. This fabric script worked fine when there was only a handful of servers, but when you have hundreds of servers it didn’t work well.

Here is how it worked.

- You would login to special deployment host, we called it the carrier.

- Make sure you are in a tmux session.

- pull down the latest code given the tag for the release.

- run the fabric script. a. This script would run in parallel across all nodes in the cluster. b. It would push the code to the hosts c. It would run the install scripts for each component d. clean up

- This process would take hours, and if a host failed it’s install you wouldn’t know until the end, and you would then need to login to the host, investigate, and repush the update after.

Since this process took all day, it limited the number of deployments we could do, so we ended up only deploying a couple of times a week.

My goal was to make this process much better in the following ways.

- faster

- more stable, repeatable, and predictable

- automatic roll back

- targeted installs (only install the service on the hosts that need it)

- more visibility

- simple to use, easy to automate in future.

With those goals, I decided to change the way we deployed the application, and this is what I came up with.

There are four main parts:

- AppTracker: the brains that manages the deployments

- Packer: Builds a self contained install package for the service (tar ball).

- Grabber: A service that lives on the host, that handles the installation of the service.

- versions: keeps track of what versions are running on every host.

The details for each part are below, but with this new process, I was able to accomplish all of my goals. Deployments went from taking all day, to on average under 2 minutes.

The main reasons for this are because of the following:

- Instead of pushing all of the code out to each node, we pull only the code that is needed to each host. downloading is much faster compared to uploading.

- We build the package once, and store in s3, vs building on each node. If the build fails, we know before we get to the host.

- We only build and deploy the services we needed vs doing all of them.

- We added monitoring and notifications to every step of the process so we always know where we were, so if something goes wrong, it is easy to fix.

AppTracker

AppTracker is a service that allows you to deploy any of our services to any hosts. You can pick a service version, along with where you want it installed. You can deploy to a whole cluster, or just a subset of nodes, using a regex.

When a request comes in, it will see if it is a recent build, if not will send the request to packer to get built.

There was a webhook setup in our version control system, that would automatically trigger new builds for new code. This made it quicker when you want to do a deployment since your code was already built.

There was am easy to use website, along with a cli, and web service for automating tasks.

Packer

Packer had support for python and node.js since those were the two languages we used at the time, but it could easily be expanded to add more.

A request would come in, it would then pull down the code, and read the config file for that service. It would see what type of build it is (python, node.js, etc). It would then do everything it needed to do, pull down dependencies etc, and build a stand alone package, and tar it up, and store in s3. It would then let app tracker know it was finished, which will then send a message on a pub/sub channel to grabber.

This might look familiar to you, it is doing something similar to what docker does today with docker builds for images, and pushing to the registry. Not quite as advanced as Dockerfiles, but along the same lines.

Grabber

Grabber lives on each host, and it knows which cluster it lives in, along with its hostname. It listens on a pub/sub channel for new requests. When it gets one, it looks to see if the message is for itself, and if so, if the version that needs to be installed is already installed or not. If it is not already installed it will install the new version.

Installation is pretty simple, it will pull down the tar file from s3, extract into the given directory. Switch a symlink and then stop the old version and start the new one. It checks to make sure it started up correctly if not, it rolls back to the old version.

It sends it’s update to apptracker, and the apptracker website in realtime, so the progress of the release. If any of the nodes failed, the person deploying will be able to see the logs from the failure in the website, and easily trigger a retry, or login to the host for a closer look.

Versions

This is a simple service that looks at all of the hosts and lists which hosts have which version of applications. This data is shown in a table on the appTracker website. With a few clicks it someone can update the versions that are out of sync.

There is a daemon on each host that gathers the information about each service and reports it back to the main service every minute. There are also nagios alerts setup so that if some conditions are meet, it will page an on call person.

Services

The services at dotCloud where written with something called cloudlets A grandfather to the docker image format. It was very hard to use, but at the time, it was the best thing available. We learned a lot of things from this project, and it helped shape Docker to what it is today.

I can’t remember when, but eventually I was responsible for managing the language and database services on dotCloud. This meant that I needed to keep them up to date with new features and versions. This was a real pain for node.js, which seemed to release a new version every other week.

Eventually we started pushing our custom service, which was a generic service that lets you do what ever you want. This became really popular, and got us thinking more about a Container as a service model, verse a PaaS model.

DiskWatcher and MemoryWatcher

On dotCloud we had some resource limits for people who ran their applications. It was fairly easy to limit memory, but disk was a little harder. We said we had limits, but we rarely enforced them, the only time we did it was when we noticed someone had way more space then they needed and it was going to consume all available space on the server.

I created a couple of tools that ran on each hosts and reported back to us the disk and memory usage for each service, and then we can group by account. When someone went over the limit, we could reach out to them and let them know that are over the limit and to clean things up. Most of the disk space issues were caused by log files. There were a few applications that would get in a bad state and easily output 100’s of GB’s of log files in a matter of hours. If we notice this, we normally got paged, went in, clean up the logs, and let the person know there app is acting weird. Since it was the same people every time, we kind of got used to it, and so didn’t they. Sometimes we just needed to restart the container, and it fixed itself.

Minesweeper

For a while we ran a free cluster, for people to try out services. Whenever you offer something for free there is always someone who will try and game it. The two biggest problems we had was running bitcoin miners and minecraft servers. minecraft servers were not against our TOS, but they usually consumed a lot of resources and caused issues for others on the hosts.

To fix this problem, we used to login to each host and see what services were using the most resources and if it was a bitcoin miner, we would stop the container, and contact the owner. We would shut it down, they would just start it back up.

This got tiring, so I wrote a program that did this automatically. It wasn’t long before they had something that checked to make sure it was up, and if it was they would automatically start it back up. We went back and forth like this until, I would hit my limit (5 times), and I would delete the app. If an account has repeat violations, they would be suspended. It was a real cat and mouse game for a while. But because it was automated, it wasn’t taking much of our time anymore, and was just an annoyance.

Hackdays

Once a month we would have a hackday, the goal of the hackday was to do something to improve the platform, and work on something that wasn’t on your current sprint plan. Here are a few of my hackday projects that I could remember:

Andrea wearing Hackday hat

help.dotcloud.com

A simple web page that had links to all of the different help options for dotCloud.

status.dotcloud.com

When there is a server crash, or an outage, the on call person would get paged, and they would start investigating what needs to get done. They are also responsible for keeping customers in the loop, so they know if they are affected, and when it will be fixed.

I made a simple website where the on call person could login, pick the servers and services affected, and then update twitter, dashboard.dotcloud.com, status.dotcloud.com, and IRC all at the same time. This was before statuspage.io, and status.io were around. Before this, it would require the person to login to each service one at a time, and post a message. This made it much quicker and easier.

This also allowed us to capture metrics to see how many outages we had, and which hosts were the most affected.

Djangocon 2012 talk about PCI compliant apps

One of my first conference talks was at DjangoCon 2012 in Washington D.C. It was about building PCI compliant web applications. I was also able to talk with people who were using dotCloud, and help answer any of their questions. I also gave out a bunch of t-shirts.

.@kencochrane explaining the morass of PCI (credit card industry) requirements in his @dot_cloud shirt #djangocon pic.twitter.com/WTJB4k3b

— Gabriel Grant (@gabrielmgrant) September 6, 2012

Here is the video if you are interested in checking it out.

The Docker Pivot

On March 10th 2013 John Costa, Charles Hooper, and I flew into San Francisco for 2 weeks, to work on a number of dotCloud projects. Little did we know what was in store for us.

On Monday morning March 11th, we gathered in the dotCloud kitchen, and Solomon got us together to talk about what we are going to be doing for the next week. We were going to be working on getting Docker ready to launch. Before that day, Docker was an internal side project that Solomon and a few other engineers were working on.

We were sponsoring PyCon, and it was the following weekend, so the idea was that we would launch Docker, and then talk with everyone about it at PyCon. It was pretty much all hands on deck. We divided into two teams. One team would keep working on dotCloud, business as usual. The other team would be all hands on deck for getting Docker ready for primetime.

I was picked for the Docker team. At this point, I hadn’t done much with Docker, so I had to come up to speed quickly. We ended up working 15 hour days. We would get to the office around 8-9am and leave 11pm-midnight. We did this every day until we left for PyCon.

I worked on a number of different things:

- helping create the docker registry

- added support for docker login

- documentation

- vagrant support

- testing

On any given day I was jumping between python, ruby, go, and Bash. It was a blur, but we got everything ready for PyCon. I was able to reserve Solomon a lightning talk slot, and he was going to use that to introduce Docker with a quick demo. We didn’t expect that many people to be at the lightning talk, but the goal was to record it, and then we can show the video. Little did we know the session was packed, and it went well.

Me (in red) hard at work with Gordon

Ken and Sam discussing how to build docker registry

Docker launch

Team #dotcloud prepping for lightening talk at #pycon.... Stay tuned for big announcement by @solomonstre pic.twitter.com/7odsaIC9Zc

— dotCloud (@dot_cloud) March 16, 2013

Solomon gave the lightning talk, and immediately right after that, a ton of people started coming over asking for access to Docker. At that point we hadn’t opened up the github repo, so people started thinking it was vaporware. We started collecting names, and giving people access to the repo on a case by case basis, but that wasn’t going to work for long, we needed to launch Docker for real, but that would require a lot more work. Which meant there wasn’t much sleep for the next week.

Bloody Monday

On Monday March 18th after a long weekend at PyCon we gathered again in the kitchen at dotCloud. Solomon got everyone together to let everyone know, that PyCon was a success, and everyone loved Docker, and he has made the difficult decision to pivot dotCloud away from the PaaS and towards Docker. There was some layoffs, and unfortunately we lost some co-workers that day, but due to the new direction, we needed to keep things lean, and needed to keep moving forward.

The goal was to keep the PaaS up and running, but we would not be adding any more features, we would get it ready for sale, and look for a buyer. We did not want to leave our customers hanging, and since it was making money it made sense to keep it as long as possible. The company was again divided into two, one for dotCloud, the rest on Docker. We were given the rest of the day off to think about the pivot, and to get some rest from a busy previous week. We would come back in on Tuesday and hit the road running, with a goal to have Docker officially launched by the end of the week.

I was assigned to the new Docker team, but I was still responsible for maintaining the PaaS, so I was working double duty. Luckily the on-call wasn’t that bad, and most of the time was dedicated to building out Docker.

.@KenCochrane "first M in revenue I will take off my hat for a whole day" /cc @docker pic.twitter.com/h7ulip5aOH

— Julien Barbier 🙃❤️ (@julienbarbier42) May 23, 2014

Docker, The Future

Once the decision was made to pivot the company, there was a lot to do, in a short amount of time. I was given a few tasks that needed to get done ASAP. One of those was a place where people could upload and share their docker images. We created the docker registry, which was an open source project that anyone could use, but we wanted to have a central location that anyone could use out of the box. We decided to call it the docker index. Since I had a lot of web application experience, I was assigned the task to build it. Since we were a python shop, and I was most familiar with Django the python web framework, I decided to write it in that. We used bootstrap for the UI and I got started.

Docker Logo

We had a popular open source project, and people liked the name. Now we needed a logo. Thatcher Peskens was tasked with hiring someone to create a logo. He created a contest on 99designs.com and the community was allowed to vote for the winner. Results of the poll

Here is the blog post announcing the new Docker logo and style.

The logo and design was very popular, and we have given away many many thousands of stickers and t-shirts to prove it.

Docker index

The docker index started off as a fairly basic web application with an API that interacted with the docker registry and the docker engine. It offered the ability to register for an account via the website, or via the docker engine. Once registered, you could push your own public docker images, and share them with the world. Over time, I added features for search, and official images and this made it even easier to get started.

For the first year or so, I was the only person who worked full time on the index, every now and then Thatcher would help me with some UX/UI stuff. Eventually we slowly added people to the index team, and even created another team for creating a central service for managing the users of Docker. We called that team docker.io. After a little while I became the engineering manager for both teams and that worked well, and we got a lot done.

Automated build system

Solomon had an idea to tie a new Dockerfile feature of docker with the index. He wanted to let people link their github repos to the index, and then when someone made a code change, automatically rebuild that project using the Dockerfile in the git repo, and push to the registry. I liked the idea, and built the first proof of concept during a hack day, and put it in production the next week. It was really popular, too popular in fact, and we had to rewrite it so that it could scale better. Dustin Lacewell took over the project and built version two, and still works on the team that maintains the automated build system today.

They have since released version 3 of the system, with a lot more features, and the ability to scale even more.

Build Triggers

The automated build system was pretty popular, and people started using it in their CI/CD chain, and because of this, they wanted more flexibility for when the automated build would be triggered. Some people wanted to run their unit tests first, and then only build the image if they passed. With the current setup, that wasn’t possible, so I created Build Triggers, which allows you to hit a special endpoint with a HTTP POST and it will trigger your automated build directly.

Repository Links

One of the things that we recommend is to base your custom images on our official images, this way you build on top of a known good supported image. The problem with this was people were not updating their images when the official images were updated. This mattered when there were security patches, added to the base image. I created a way for people to link their repositories to another one, and if that one changed, it would automatically trigger a rebuild of the child image.

This was also another very popular feature, and with it caused the Automated build team some headaches, because whenever an official images was updated, it would trigger a ripple effect and stampeded the automated build system with a ton of builds all at once. They have since improved the scalability of the automated build system to better handle these events. We also put in place some communications between the official image team and the automated build team, so that they give them a heads up when a release is coming, so they can make sure they have enough capacity to handle the load.

Collaborators

This allowed you to give access to another user to push to your image, and was pretty popular, but people wanted more. So we started working on the organizations and teams feature.

Docker Hub

Right before the first DockerCon in San Francisco we decided to rebrand the docker index into the Docker Hub. This required a lot of work on merging two different websites (docker.io and index.docker.io) into one website hub.docker.com, and making sure the UI/UX was the same between the two sites. This took a lot of work, but we were able to make the move, and it made the website look much nicer and added some features that we had been working on for a little while.

Private repositories

From the beginning of docker index, I had the concept of a private repo, this allowed you to push up an image, and not make it public. I had only exposed it internally to docker employees to try out, and to make sure it really worked as advertised, we wanted to make sure only the people you wanted to give access too, could access it. This was also a feature we wanted to charge for, so in order to get this working, we had to add a billing component.

Billing

Before we could start charging for the hub we needed a way to collect money, so I built a billing service that allowed people to subscribe to a plan and they would be automatically renewed at the end of their billing cycle. After going back and forth with Recurly and Stripe, we ended up with Recurly because of a few features strip didn’t have at the time. Once Billing was complete, we were able to start charging people to use the hub, and work our way to start paying for the huge AWS bills we have been generating due to all the traffic for the public repositories.

Organizations and Teams

Once we released private repositories we needed a better way to share them with others, so we also released a way to create an organization account and to group people into teams and share things based on the team instead of someone individually. We also added a way to convert an user account into an organization account. Most of this work was done by (Josh Hawn, Thatcher, and John C) as part of the docker.io project, and I helped integrate it with the docker index code.

Docker Hub 2.0

When we started working on the docker hub, our goal was to start breaking up the monolithic application into smaller micro services, and we started doing that, but one of the issues that was causing us problems was the front end. Serving a common front end across multiple services wasn’t ideal. The way you get around this, is that you break up the front end from the backend services and use APIs between the two. Hub 1.0 had a deadline that couldn’t be moved, so we were not able to do it the ideal way. So the goal was to get Hub 1.0 out the door, and then work on Hub 2.0 which was breaking up the hub frontend and backend, and release the new frontend.

One issue was that most of the people working at Docker were backend folks, we had very little front end experience. So we went out and hired some people who knew what they were doing. We first hired Chris Biscardi , then hired Nathan Hsieh, and Arunan Rabindran. The three of them along with some designers, Nick Kraly and Josh South designed and built the front end, while we worked on providing the backed APIs to them.

It took a lot longer then we had planned, but we finally launched a hub 2.0 beta, and then switched over to the new hub 2.0, which is the hub that you see today. For more details, there is a great blog post from Chris UI at Docker.

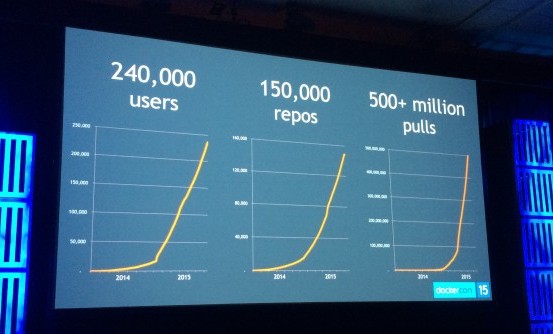

Docker Hub Scale

One of the issues that we had to constantly deal with was docker was growing way faster then anyone expected, and with that the demand on the docker hub. The amount of docker pulls was growing and along with it the bandwidth. Here is a little chart showing how it has grown over the years.

Docker Hub growth curve (June 2015)

Docker Cloud

In October 2015 Docker acquired Tutum and I was part of the group of people who did the due diligence on the company, and in doing so, I became very familiar with their products. I was also the most familiar with the Docker Hub, so it just made sense if I was the one that helped integrate the two products into what we now call Docker Cloud.

The Tutum folks were based in Spain and New York, and since I was in Maine, that the same timezone as New York, and was only a 5 hour difference compared to the 8 hours in San Francisco. I worked with them to get them access to everything they needed so that we could have a nice tight integration between our two services.

One of the things that we needed was a way to charge people (metered billing) for this new service, and current billing system wasn’t setup for metered billing. Since I wrote the first version of the billing service it only made sense that I work on the second version.

I created a new micro service called billing_v2 that had all the original billing features that the hub still used, and added the new features that docker cloud needed, and then we switched the hub and the cloud to use the new billing service. This was a big task in a short amount of time, so I was also able to get some help from Matt Tescher, and John Costa.

Once the billing feature was complete and the cloud/hub integration was done, we went live with Docker Cloud.

Conferences

Since I was one of the only employees on the east coast I was able to go to a lot of cool conferences and talk about Docker. Here are a few of the talks I have done over the years.

DjangoCon US 2013

I was able to give an intro to Docker talk at DjangoCon US 2013 in Chicago. I actually met Dustin Lacewell after my talk, and convinced him to apply for a job at Docker. Here are my slides, and blog post and video:

Rackspace Solve

Our CEO Ben Golub gave a talk at the Rackspace solve conference in San Francisco, and it was very popular, and they wanted to have the talk at their New York conference. Ben wasn’t able to attend, so I was able to fill in for him.

This was my first conference talk that wasn’t in front of a room full of developers. This was targeted more for C level executives, so I had to dress up (I couldn’t wear my hat!), and I couldn’t hide behind a podium.

Since the talk with in NYC, I decided to fly down in the morning, and then fly back at night. RackSpace sent a car to pick me up at the airport. This was also a first, I normally take the subway into town, but I didn’t want to turn down a ride right to the door, and it would give me time to practice my talk one last time. The problem was that there was so much traffic, it took me 2 hours to get to the conference, and I arrived about 5 minutes before I was scheduled to go up on stage. Just enough time to go to the bathroom, get mic’d up and jump on stage.

Because I was in such a rush to get up on stage, I wasn’t aware that they had me scheduled for a 30 minute talk, when originally we agreed I was going to have a 40 minute talk. This caused a problem, I had prepared a 40 minute talk, and needed to give it in a 30 minute slot. Nothing more complicated then trying to dynamically remove 10 minutes from your talk on the fly. I think I did alright, but it did prevent me from giving my best. Here is more details about my talk, and the video.

PyCon 2014 in Montreal

I gave a poster session on Docker at Pycon in Montreal. This was pretty cool, it had been a while since I had been to Montreal, so it was nice to see the city, and help folks with docker. I ran into Nick Lang again, and convinced him to attend DockerCon, and eventually convinced him to come and work with me at Docker.

I came to the conference with about 50 t-shirts, that was all I was able to carry in my luggage. When I got there, I put the box down, and turned around to talk with the large crowd that gathered, and before I knew it, I turned around and all of the shirts were gone. It was crazy how fast they went.

@KenCochrane draws a crowd @docker poster session #pycon #pycon2014 pic.twitter.com/fekUwt6uWA

— Brad Clements (@bkc) April 13, 2014

DockerCon 2014

DockerCon 2014 was our first DockerCon, and it was based in SanFrancisco, and it was a lot more popular then we expected. It was a lot of fun. I helped with the conference party in an art gallery, and we had a photographer taking everyones pictures. The picture of John and I jumping for joy is shown below.

I didn’t have to give a talk at this conference, but I helped to create the live demos, and also launch the docker hub.

check out @johncosta and I jumping for joy at the #dockercon after party. pic.twitter.com/sMcWCYmtZB

— Ken Cochrane (@KenCochrane) June 12, 2014

Even the @docker investors are having a blast at #dockercon @dschol @trinityventures @DockerCon pic.twitter.com/wrVSIetqY5

— Ken Cochrane (@KenCochrane) June 10, 2014

DockerCon Europe 2014

In 2014 we had DockerCon Europe in Amsterdam, and I had the change to attend. It was my first trip to Europe, so I wasn’t sure what to expect. It was great, and I had a lot of fun. I hope to bring the family back sometime in the future.

On the way to DockerCon CoreOS released a blog post that caused a stir in the Docker community. Some people called it the start of the container wars. This wasn’t the way most people expected to spend the first few days before the conference, but as a company, we all came together and still put on a good conference. We also learned a lot that day, about how to, and how not to handle tough situations as a company.

Here is a video of the talk that I gave about the Hub.

One thing I really liked, was all of the different types of food I normally can’t get back home. Probably the best reason to travel, if you ask me :)

hmmm Back Bacon in Amsterdam

DockerCon US 2015

DockerCon US 2015 was back in San Francisco, and once again, I was able to attend. We launched the Hub 2.0 beta at this dockerCon, and we spent a lot of time getting it ready, and it was well received. I also gave a talk with bc Wong here is the video.

DockerCon Europe 2015

In 2015 DockerCon Europe was in Barcelona Spain, and lucky enough Tutum’s offices were not too far in Madrid. So the plan was to go to DockerCon and then take the train over to Madrid to work with the Tutum folks out of their office for a couple of days and then fly home.

This was the first conference in a while I didn’t have to give a talk, but I made up for it, by helping with other tasks. One of the tasks was stuffing all of the different goodie bags that we hand out to each attendee. I also helped with registration, staffed the docker booths, and went to one of the advisory board meetings.

As a gift for every person who attended DockerCon we had a partnership with Yubico to give everyone a yubikey.

The problem was that the Yubikeys that we were going to give to everyone were stuck in customs. To solve this, they had someone fly to Spain with a new batch in their carry on luggage, and hand deliver to the conference. The problem was the new ones were not assembled so we got some volunteers and we put them together.

Building yubikey packages

Once that was done, we needed to tap them to the chairs in the auditorium where the guests wouldn’t be able to see them until we said, reach below your seat. This was our Oprah moment.

There was just an Oprah moment at #dockercon @docker gave everyone a new @Yubico pic.twitter.com/Huolqi1Hkg

— Ken Cochrane (@KenCochrane) November 16, 2015

DockerCon Seattle

I wasn’t able to attend DockerCon US 2016 in Seattle, but the project I was working on, was launched there. Check out the keynote video, to see Docker for AWS.

Meetups

Besides conferences I also gave a bunch of talks at different meetups around the north east, and I even started a few meetup groups myself. Docker New York City, Docker Boston, and Docker Maine.

While I was in the NYC for the first Docker NYC meetup, I stopped by the offices of Digital Ocean, and helped them build a Docker one-click-app to make it easy to use Docker on their service. It was really nice of them to let me hangout in their office for the afternoon. To thank them, I sent them all Docker shirts.

Ken with Ben and Moisey Uretsky Digital Ocean co-founders

Digital Ocean team wearing Docker shirts

Docker Core

For the past 3 years I had been working on the Docker registry, index, and hub. When I was working on the cloud, and getting my hands dirty again, I realized I really missed that. I liked being an engineering manager, but I liked being an engineer even more. I also realized that I needed to start working on something different, and so after talking with Solomon and Sam Alba, I was able to move over to the Core team and help them where they needed help.

Docker 1.11 release

One of my first tasks on the Docker Core team was to help with the Docker 1.11 release. Docker 1.11 was the first release that was built on top of containerD, and because of this, the docker packaging needed to change to support installing multiple binaries. It had been a while since I had worked on rpm and Debian packaging, but I dove in head first and did what I needed to do to help get the release out the door. This was a lot of fun, and got be reintroduced to the docker engine.

Docker CS releases

Docker CS releases are releases that we commercially support, and back port patches so that companies don’t have to upgrade as fast as they might want too. I helped with the CS releases by documenting and updating some of the tools that they use. I didn’t work on this project for that long, but it gave me insight into how this all worked, with was very help information.

Docker for AWS

For the past year I have been working on the editions team building out the Docker for AWS product. This has been a lot of fun, I have learned a lot about AWS, more then I ever thought was possible. I was also able to go to AWS Reinvent in Las Vegas for the first time. This was the largest conference I have ever been too, it was spread out across 3 different casinos on the strip, and it took 25 minutes to walk from one set of talks to another. One day maybe DockerCon will be that big?

What’s Next?

Now that I have been with Docker for 5 years, I sometimes wonder what will I work on next. I’m not really sure, but I’m sure it will be awesome. Sorry for the long post, but I guess it shows all that we have done in the last 5 years, and I’m sure I missed a lot as well.

If you liked this post, you would probably like Jérôme Petazzoni’s Post from dotcloud to docker.